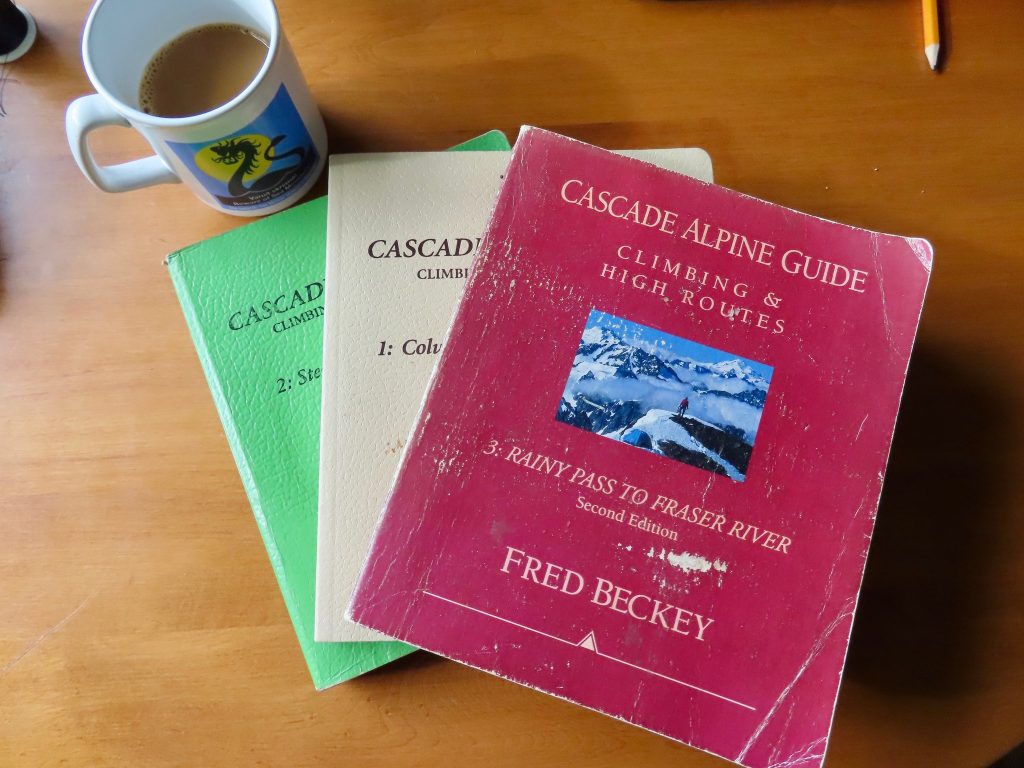

My education about the geology of the North Cascades began with the climbing guidebooks of the late and great Fred Beckey, the legendary dirt-bag climber and curmudgeon. Collectively known as “Beckey’s Bible,” the three-volume Alpine Guides were the first books I bought in Seattle, when I moved here in 1994. I considered them a doorway to adventure. They are without a doubt three of the most influential books in my life.

Beckey’s guides introduced a whole generation of pilgrims to these mountains. Although the primary purpose of the books is to describe climbing routes, I found myself drawn to his introductions as much as his route descriptions. He goes into considerable detail regarding the geography, geology, botany, and history of the different sub-regions of the Cascades.

Beckey is famous as a cantankerous climber, but definitely underrated as a wordsmith. Consider, for instance, this sentence describing Mount Shuksan “…rising in a spearhead of dark rock (greenschist), carved by elements into deep cirques and ragged aretes, adorned with chaotic hanging glaciers, frosted and tiered with snow plaques and ice patches.”

After reading that, I knew right away that I had to climb Shuksan. And I did climb it, and it was memorable for many reasons—not the least of which was the most splendid outdoor latrine I’ve ever had the privilege to use. (I bring up this usually private moment only because while visiting this latrine I witnessed the most spectacular icefall I have ever seen.)

I knew from that first description that I needed to get up Shuksan, but what I didn’t know right away is how deeply in love I would fall with the area all around the mountain, an area of geological mysteries, record-breaking snowfall, botanical oddities, perfect alpine lakes, and scenery that is as grand as any place in North America.

While I’ve only reached the summit of Shuksan once, I’ve made repeated trips to three neighboring peaks that are less lofty but no less magical: North Twin, Tomyhoi Peak, and Ruth Mountain. And I make an annual pilgrimage to swim in the lovely Lake Ann and climb around on the ice of the Lower Curtis Glacier, nestled in a cirque on Shuksan’s western flank.

So while Shuksan richly deserves to be praised in poetry, prose, and song, while it deserves to have dissertations and books written about how it came to be, this blog post is mostly about the land around it. More specifically, it is about two incredible and peculiar geological features that sandwich the great mountain.

One of these features is immediately to the west of Mount Shuksan, and a hiker making his way to the Lower Curtis Glacier will cross it. The other is just to the east of Shuksan, and a climber standing on the summit of Ruth Mountain will be standing right in the center of it—likely without even knowing it.

Both of these features are the result of geological events of almost unimaginable drama and violence, events that fundamentally altered the landscape. And yet, for all their impressive magnitude, both features have been so thoroughly eroded over time that they will be pretty much invisible to the eye that is not trained to see them.

I am speaking of ancient calderas.

***

Just to the east of Mount Shuksan, Ruth Mountain is a bit of an anomaly—a relatively gentle, smooth-sloped triangular peak that stands out conspicuously in a sea of jagged rock draped with precarious and fractured glaciers. When I stand on the summit of Ruth, gazing at the razor-sharp skyline of the Picket Range and the dark and forbidding Nooksack Tower, I’m amazed that I could enter the inner sanctum of such a place with relative ease.

Ruth’s easygoing aspect and straightforward approach is unusual in a region where climbing and suffering are synonymous. The welcoming character of the mountain is fortunate for an aging solo climber; it means I don’t have to rope up, and I can easily do it in a day, even with a wonky knee and a growing old-man belly.

(Because the route up Ruth crosses an active glacier that has a few easily avoidable crevasses, many people do rope up on it. It is considered more than a casual hike, and some guide services charge clients in the neighborhood of $800 to reach its summit. But it is not a hard ascent, is usually done in a day, and poses minimal risk to anyone with common sense, good boots, and some skill with an ice ax.)

The summit offers a stupendous vantage of some of the North Cascades’ most impressive features, such as the aptly-named Picket Range and the austere Nooksack Cirque with its hanging glaciers and seracs poised to come crashing down into the cirque at any moment.

Indeed, it almost seems unfair that such a summit can be reached by an uncomplicated day-hike, when so many other nearby summits (with lesser views) require bushwhacking through nearly impenetrable forests, side-hilling on diabolical scree, and threading your way through gullies of shattered rock. A trip up Ruth seems like I’m getting away with something.

Often, it is a precipitous peak surrounded by gentler neighbors that draws the eye and holds a viewer’s appreciation. But I find Ruth’s shape to be a lovely and satisfying contrast to the dramatic topography around it. Its shape is related, of course, to its history. Ruth looks different from the neighboring peaks because it is different.

Like the ugly duckling who was really a swan and not a duck, Ruth is not kindred to the peaks around it. While the peaks around it are the non-volcanic and crumpled result of tectonic plates colliding, Ruth—along with its modest neighbor to the north, Hannegan Peak—is what remains of an ancient volcano. And Ruth sits in the middle of a caldera known as the Hannegan Caldera. Its creation was about 3.7 million years behind us.

If you’ve been to Ruth, you may be surprised to learn this. Standing on the summit and looking over the landscape of rugged peaks and deep glacial valleys, it does not look like you are in the middle of caldera. But there are signs, for those who know how to read them.

The event or sequence of events that created the caldera was bizarre, kind of delightful to contemplate, and unique in the world as far as geologists can tell. At least they haven’t yet found evidence of a similar occurrence elsewhere. While calderas are not all that uncommon on the face of the earth, the Hannegan Caldera holds a special distinction: It is the only known “two-phase, reciprocal, double-trap-door collapse caldera” in the world.

Wow. That’s a mouthful. What the heck does it mean?

***

On the face of it, there is nothing exceptional about a caldera (although they are exceedingly cool). Calderas occur where potent volcanoes obliterate themselves in an explosive eruption, thus emptying a subterranean chamber of magma. The roof of this chamber then collapses, either in whole or in part, creating a depression that is akin to a crater, but much bigger.

The sunken area is most often roughly circular, although the shapes vary. A caldera might look more like a football, or a kidney, or an amoeba, or a jellybean. Sometimes resurgent volcanic activity will raise bumps or cinder cones within the caldera. Geysers, boiling mud pots, and fumaroles indicate that plenty of heat is not far beneath the surface, and future eruptions are possible. Often, the caldera will fill with water.

As a chain of impressive subduction-zone volcanos, the Cascade Range holds its share of calderas. The most recent, most famous, and most visible one is in Oregon, where a stratovolcano in the style of Rainier, Baker, and Adams erupted about 5700 years ago, leaving behind the deepest and one of the most beautiful lakes in North America.

Crater Lake is the most recently formed caldera in the Cascade Range. Incredibly photogenic and instantly recognizable, it is a poster child for calderas. The lake was formed when Mount Mazama obliterated itself in an eruption that geologists estimate as a solid 7 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index.

A 7 on the VE scale is a damn big blast, by the way. Enough to cover most of the USA with ash. In our lifetimes, there has not been a 7 anywhere in the world. The largest eruption in the past century was Mount Pinatubo, in the Philippines, in 1991. It was a 6. There have been a handful of sixes in human history, including the infamous Krakatoa, in 1883.

The largest eruption in several millennia was Tambora, in Indonesia, in 1815. It was a 7. The eruption that created the caldera of Santorini and probably also birthed the legend of Atlantis, circa 1600 BC, is estimated to have been a 7. And that’s it—just those two. They don’t get any bigger than that for the duration of recorded human history.

I should mention that a 7 is not just a little bit bigger than a 6. The scale is exponential, so a 7 is ten times greater than a 6. The VE scale goes to 8, and an 8 is commonly referred to as a ‘supervolcano,’ although the term ‘supereruption’ would be better, since eruptions of such magnitude are not always associated with a single discernible mountain peak. The last time an 8 rocked the planet was 27,000 years ago in New Zealand, and the most recent Yellowstone eruption of this size occured 640,000 years ago.

Mount St. Helens, in 1980, was only a 5. I say only as if a 5 were merely a hiccup. The two calderas that are on both sides of Mount Shuksan, the Hannegan and the Kulshan Calderas, were both created by explosions estimated to be 7 on the VE scale. As the crow flies, they are less than eight miles apart, and Shuksan is placed squarely right between them. Mount Shuksan has definitely witnessed some dramatic action in its time here on earth! If a mountain could talk, what stories it would tell.

***

This seems as good a time as any to talk about time. And size, too. And power.

I’ve hiked through both the Hannegan and Kulshan Calderas on many occasions. On every trip, I stop to admire and photograph the alpine wildflowers. On the way to the Lower Curtis Glacier, on a ridge just above Lake Ann, there is a slope that hosts a smattering of Saxifraga tolmiei, also known as Tolmie’s Saxifrage. It is a delicate and tiny flower, hunkering close to the ground. It thrives in the snowiest of locations, and is endemic to the Pacific Northwest.

From this ridge of flowers, you can see most of the million-year-old Kulshan caldera, with Mount Baker beyond it, to indicate the possible site of the next big hole in the ground. The flowers on the hillside are lucky to last a month before they shrivel.

An alpine flower such as Saxifraga tolmiei lives for a handful of years. A flower on the plant lives for maybe a month before it shrivels. Blink of an eye—but long enough to get pollinated by a bee, develop its seeds, and broadcast them across the waiting ground. The bumblebee that fulfills the purpose of the flower also lives for a short summer season. Long enough to do its work.

Are we much impressed by age? Or by size? In what way do we understand power? There is power in a VE7 eruption. There is power in an earthquake, or a tsunami, or a river of ice. There is a different kind of power in the saxifrage blossom and in the bee that pollinates it.

It’s been my experience of life that significance is not measured solely in terms of duration. Neither is it reckoned in terms of size. Significance is a subjective assessment, based on what is in the heart and soul (if I may be permitted to use such a mushy term) of the one making the assessment.

Consider a dog that has the lifespan of a decade, but lives on in the heart of a human who gave it a name. Consider a beloved child whose life is cut short by illness or accident; she is on earth for only a few years, but is of greater significance to her mother than any thousand-year-old tree or million-year-old mountain. Consider a single afternoon that, for one reason or another, you carry with you like a treasure. Consider yourself.

Each creature and even each caldera is one part of a larger story of interaction and inter-being that encompasses all of time.

In the wet forests of the Cascades, I am always entranced by the ephemeral blooms of mushrooms that are, quite literally, ‘here today and gone tomorrow.’ But the fleeting fungi is just the fruiting part of an underground web of mycelium that persists under snow, through seasons of drought, through times that seem barren.

In similar fashion, a single aspen tree—a short-lived species—scuttles its golden spade-like leaves in the sunlight for a mere fifty years or so before it falls to the ground and transitions to soil. But a single tree may be part of a grove, and a grove has characteristics of a living organism. The life force of an individual tree is carried on through the grove the way water from a thousand small creeks merges in a river. Hard to say where anything ends.

In trying to imagine and write about geological history, it is easy to compress a million years into a moment, as if on a Tuesday there was a certain landscape, and then—Boom!—on Wednesday there was the Hannegan Caldera where yesterday’s meadow had been.

It’s easy to imagine the distant past as one rapidly occurring cataclysm after another. It’s easy to picture a pell-mell succession of eruptions, floods, meteors, climate shifts, extinctions. But do we imagine life being placid and serene for a pterodactyl in the Mesozoic? Or for a Woolly Mammoth in the Pleistocene?

When describing landscape-shaping events, I’m tempted to resort to comic-book exclamations: KABOOM!!! KAPOW!!! CRAAACK!!!. I’m tempted, also, to visualize them as discreet, single events. For instance, in regard to the plate tectonics that creates mountain ranges: India plows north through the Indian Ocean, slams into Asia, and just like that—OOOOF!!!—the Himalayas are thrust skyward. Or, closer to home: a big slab of ocean floor basalt slams into North America and then is transformed, by geologic wizardry, into the greenschist crags and towers and summit pyramid of Mount Shuksan. PRESTO!!!

But when that chunk of ocean floor basalt that is the genesis of Mount Shuksan“slammed” into North America during the Mesozoic era, it’s not as if a human observer (a time-traveller, of course), could have walked out of her palm-frond hut on the Pacific coast, and watched a chunk of land crash into the beach like an out-of-control ferry coming too fast into a dock. She wouldn’t see that basalt transformed by pressure and heat, then crumpled and folded and thrust 9000 feet into the air. She probably would have seen just another pleasant Mesozoic sunset. Heard the plaintive cry of a pterodactyl. If we could squeeze time and let its essence drip out, what would that essence be? The earth is inconceivably violent and sublimely peaceful. Simultaneously.

And what about the slice of time that we inhabit, right now, in 2023? It is probably more cataclysmic, more pivotal, more dramatic, than any comparable slice of time from the past. For instance, what we may perceive as a slowly-unfolding change in climate is, in terms of the earth’s rhythms, happening unbelievably fast. Faster than such changes have happened before.

***

So, back to that intriguing phrase “two-phase, reciprocal, double-trap-door collapse caldera.”

It helps to take it one word at a time. The relevance of the word ‘collapse’ has already been established; a caldera is formed when an area of land that sits atop a hollowed-out subterranean chamber collapses. What does ‘two-phase’ mean? It simply means that the collapse of the caldera occurred in two distinct phases, separated in time, rather than as one event.

Now, let’s move on to the idea of a trap door. Maybe the best way to proceed is to conjure up the mental image of the entrance to the lair of a trap-door spider. A trap door is, essentially, a flap. Just like a flap of skin after an injury, only it’s on the skin of the earth. For most of the perimeter of the flap, there is a discontinuity in the skin, a crack in the earth. But on one end, the ground is unbroken and continuous. This forms a hinge.

Imagine a giant, somewhat circular chunk of land that sits above an empty chamber. Prompted by gravity, the land begins to sink. As it does so, cracks form around the perimeter of the circle. They are called faults. But on one end of the circle, faults do not form, and the structural integrity of the land holds it up and inhibits the collapse. In other words, there is a sort of hinge on one end of the caldera. As a result, the collapse is lopsided, far more pronounced on one end than on the other. More of a slump than a uniform drop.

This is where the significance of the descriptor two-phase kicks in. Keep in mind that in geologic time, phase one doesn’t happen on Tuesday, followed by phase two on Wednesday. Phase one and two may be separated by tens or hundreds of thousands of years. Enough time can elapse between phases for more volcanic activity to occur within the caldera.

Magma chambers can refill, raising a large bump within the caldera. More eruptions can occur, emptying the chamber again. Another collapse occurs. It happens, once again, to be a trap-door collapse, where the sinking happens on only one side. Only this time, the side that collapses and the side that is hinged are reversed. Voila: A double-trap-door collapse. It is reciprocal because the two sides take turns.

***

Although local geologists know them, neither the Hannegan nor the Kulshan caldera are well-known among the general population. They are certainly a far cry from famous. But there are some famous calderas all around the world.

For instance, the city of Naples, Italy, is cradled inside a mammoth caldera known as Campi Flegrei. It’s a risky place for three million people to live. The still-active volcano of Vesuvius sits on the edge of this huge caldera, giving a daily reminder to the citizens of Naples that there are no guarantees in life.

Elsewhere in the Mediterranean, the circular arrangement of the Greek islands of Santorini hints at a caldera that is now filled by the sea. The eruption that created this caldera may have been the event that gave birth to the legend of Atlantis.

In Yellowstone National Park, three enormous and overlapping calderas bear testimony to the explosive past of a “supervolcano” that sits above a hot spot in the earth’s mantle. Yellowstone Lake partially fills one of these calderas.

In California, the ski town of Mammoth is nestled inside the huge Long Valley Caldera. The center of the Long Valley Caldera holds some delightful hot springs that would be even more enjoyable if they were not pretty much constantly occupied by aggressively naked and often inebriated climbers, hipsters, shamans, and shred-betties.

Despite the stellar scenic qualities of these two obscure calderas of the North Cascades, the reason they are not as well-known as the other examples mentioned here is simple enough: they simply aren’t easily recognizable as calderas.

I’ve mentioned that a person standing on the summit of Ruth Mountain would have trouble realizing that he is inside a caldera. It’s equally true that a hiker laboring up the slope to Lake Ann, looking back at the gleaming snow cone of Mount Baker, would have trouble realizing that the valley she is looking across is, in fact, the center of the Kulshan Caldera.

Many of Earth’s calderas are much older than the Hannegan and the Kulshan, yet remain clearly recognizable. In contrast, the two calderas that flank Mount Shuksan are difficult to discern just by looking at the landscape; geological sleuthing is required. Why is this? The answer has to do with another reality of the North Cascades: the presence of ice.

It can be hard to recognize an ancient caldera in a place where aggressive glaciation has scoured the land. During recurrent ice ages, glaciers thousands of feet thick advanced and retreated several times, removing softer rock and leaving more resistant rock behind. When the caldera rim has been breached, tongues of ice widen and deepen the breach. After the ice is gone, rivers assume ownership of the valleys. Lakes drain away.

Other processes that sculpt a landscape continue. Further volcanic activity can alter the caldera’s appearance, raising new mountains within the caldera. It may no longer look anything like a bowl. A hiker can be standing smack dab in the middle of an ancient caldera and never know it. But there are geological signs for those who can read them. There are ways that rocks tell the story.

One way that rocks tell the story is with thick deposits of a volcanic rock called ignimbrite, which is a blend of volcanic ash and pumice, welded together. (If you’ve heard of volcanic tuff, it is the same thing as ignimbrite.) The name is derived from a combination of the Latin words for fire and rain. The name bears no relation to James Taylor; it has to do with the origin of ignimbrite in a pyroclastic flow from an explosive eruption.

The rock that composes Mount Shuksan is very dark. It is greenschist, which is a metamorphic rock formed from basalt that has been altered by pressure and heat. On a gloomy, misty day, this dark rock adds to the brooding mystique of the mountain. In contrast, the ignimbrite deposited by caldera-forming eruptions is a light-colored formation, ranging from beige tan to grey. It looks frothy, like hardened meringue on a petrified pie.

Ignimbrite is evident on the south slopes of Hannegan Peak; from the slopes of nearby Ruth Mountain, you can see it glowing in the light of sunrise. It is also evident in the watershed of Swift Creek, eroded into steep gullies. In both cases, the light rock is visible from a distance, and it tells the tale of two calderas.

***

That tale is a single chapter in a long and complicated story. The story is as long as the earth is old. I intended, in this blog entry, to only dip into the chapter about two calderas in one of my favorite corners of creation. But I must also say a bit about Mount Shuksan, that incomparable mountain first introduced to me in the words of Fred Beckey, who had spent more than a few days on its slopes. So the last part of this blog entry is not about calderas at all. It recounts some geology that is older and stranger than calderas. It is about the formation of the mountain range that is most significant to me, which is to say: closest to my heart.

In addition to Mount Ruth and the Lower Curtis Glacier, another one of my favorite places in the shadow of Shuksan—I’m not embarrassed to call them my sacred places—is Tomyhoi Peak, which is a short distance to the north. I try to go there once a year, and a year that I miss this hike feels just a bit incomplete.

I’ve written at length about Tomyhoi Peak before, so I won’t do it here, except to quickly mention that among its charms are a fern grotto that boasts greater fern diversity than any place in North America, incomparable blueberry meadows, and a basin of jewel-like tarns that melt out in late July, and are perfect for an icy baptism.

I bring up Tomyhoi, briefly, because the view of Shuksan from Tomyhoi is splendid, and in one notable way quite different from the views of Shuksan that you get from either Ruth or the Lower Curtis Glacier. There is no place better than the upper ridge of Tomyhoi if you want to view craggy Mount Shuksan side by side with the other great mountain of this region: Mount Baker, the volcano, the reigning queen.

I love this view. Baker (or Kulshan, to use its indigenous name) and Shuksan, equal in beauty, are utterly unalike. One is clearly a volcano; the other clearly is not. I love the North Cascades, in part, because of this contrast. It suggests a long and complex history. The volcano is a recent creation, a youngster, merely the most recent expression of the forces that created the two calderas, and Rainier, and Glacier Peak, and a long line of ghost volcanoes that have come and gone, leaving their signatures in layers of ash.

But that other mountain, the craggy one… How did it come to be? And why are they right next to each other?

For a long time, the North Cascades was one of the least understood mountain ranges in America, at least in terms of a coherent narrative of its origin. Sure, the volcanoes were easy enough to understand, but the jagged mountains in northern Washington are, for the most part, not volcanic. The range seemed like a jigsaw puzzle where even after it’s assembled, the pieces don’t seem to fit. At least, the assembled picture seems more like a Picasso than a Rockwell.

Before the theory of plate tectonics was widely understood and accepted (which is to say before the 1960s) the geology of the North Cascades was pretty inexplicable. This mountain range was in many respects a perplexing jumble of rocks that didn’t belong together. One sub-range was composed of a granite batholith, like the Sierras in California. Another sub-range right next to it was composed of metamorphosed sediments, or sea-bed basalts, or even an oddball rock like Dunite, which is rare on the surface of the earth, but common in the Mantle. These patches of different rock types seemed pasted on to each other with no rhyme or reason.

But there is a reason, and it begins with a key fact to keep in mind when contemplating the jigsaw puzzle: A subduction zone right off the coast. A place where one of the earth’s crustal plates collides with another, and then keeps going, diving deep under the North American continent, experiencing heat and pressure, buckling, folding, changing before it is thrust high into the sky.

And in addition, just to make things even more interesting, the presence of south-to-north strike-slip faults (like the San Andreas Fault in California) that over time shift whole chunks of land northward. In some places where plates meet, they don’t collide; rather, they slip sideways. The Straight Creek Fault, which passes near Mount Shuksan, is one such south-to-north strike-slip fault.

Plate tectonics was indeed the key to the puzzle. In the words of an unnamed contributor to Wikipedia, “…the new science of plate tectonics illuminated the ability of crustal fragments to ‘drift’ thousands of miles from their origin and fetch up, crumpled, against an exotic shore.”

Some uncredited authors, like some dirt-bag climbers, have a way with words.

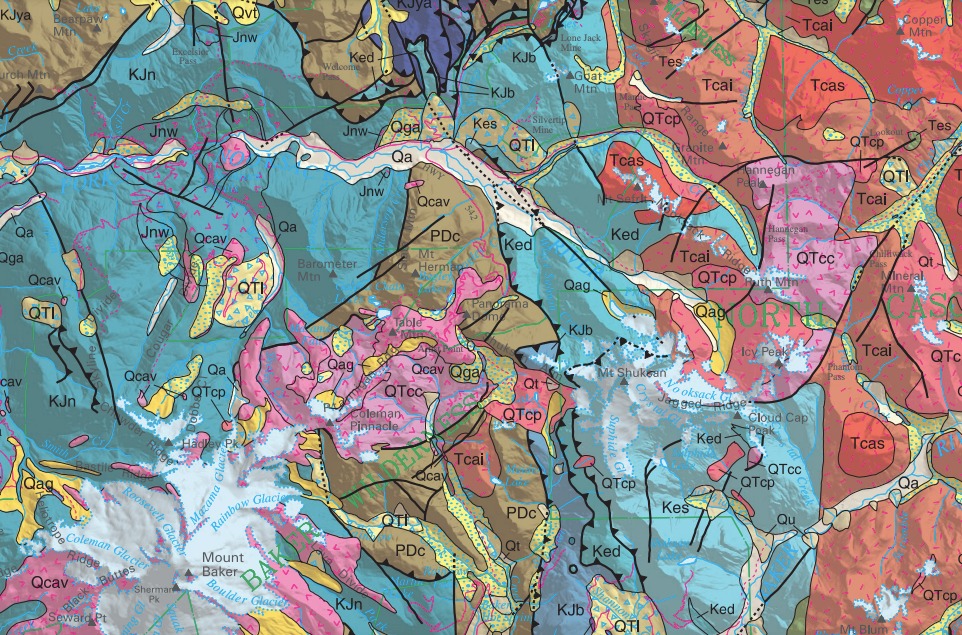

The North Cascades are as geologically complicated as any mountains in North America, and the area specifically around Mount Shuksan is especially so. A geologic map of the area presents a tapestry of slivers and wedges, shards and blobs. It’s a collage of chaos, a mosaic with no discernible pattern. A mess.

Mind you, the word ‘mess’ is not a geological term. A geologist might refer, instead, to plutons and terranes, deposits and intrusions. She might go on to explain that intrusions come from below, while deposits are laid down from above. A pluton is a mass of magma that didn’t erupt on the surface, but rather solidified underground; a terrane, on the other hand, is a chunk of land that moves laterally, thanks to the phenomenon of continental drift.

But then she might concede, as well, that… yeah, it’s a bit of a mess. A beautiful, fascinating mess. Why is it so messy? It’s messy in large part due to a phenomenon known as exotic terrane accretion. What the heck does that mean? Well, turn the word accretion into a verb: accrete. To accrete is to add one thing to another. Slap it on, glob it on, paste it on. So an accretion is a bit of something that is pasted on to another bit of something. But what is a terrane, and why is it exotic?

I’ll let a geologist explain it. In the words of Dr. Ralph Dawes of Wenatchee College, “A terrane is a group of related rocks that formed together in one area, do not show any relationship to the other rocks around them, and are separated from the rocks around them by faults. Terranes range in size from a few square miles to thousands of square miles. Plate tectonics explains how terranes can be moved across an ocean and added to a continent. Because terranes come from a distant location they are often referred to as exotic terranes.”

And there you have it: The North Cascades are made up of bits and pieces of land from all over the Pacific Rim, plastered together. Terrane is another word, a snazzier word, for a ‘crustal fragment.’

Starting in about the 1970s, a few geologists began employing the new technique of paleo-magnetic analysis in order to determine the origin of rocks. This led them to construct what seemed, at first, a theory a little too implausible to believe. But, over the past few decades, more and more evidence is lining up to support it. What’s the theory?

I like the way the geologist J.N. Carney puts it: “It was soon determined that these exotic crustal slices had in fact originated as ‘suspect terranes’ in regions at some considerable remove, frequently thousands of kilometers, from the orogenic belt where they had eventually ended up.” The movement of these terranes was not just in one direction; in addition to ‘slamming’ into North America, they also ‘slipped’ northward in much the same way that Californian real estate on the west side of the San Andreas Fault is currently slipping northward toward Seattle.

I love the phrase ‘suspect terranes.’ Hmmmm…. Where are your papers, you wandering chunk of granite?

Simply put, these fellows were suggesting that a sizable chunk of the Cascades—the mighty Stuart range batholith, to be precise—originated in Baja California. The alignment of magnetic crystals in the granite of Mount Stuart—crystals which are sensitive to the position of the magnetic North Pole—functioned as nature’s own GPS. They indicated the latitude at which the rock was formed.

What at first seemed a crackpot theory has now wandered into mainstream acceptance as more and more evidence accumulated. Such is the way of geology. Drifting pieces of land that, one after another, have plastered themselves onto the western edge of what is now Washington, are referred to as ‘exotic terranes.’ They are exotic because they come from far away. The granite of iconic Mount Stuart, a dramatic peak that exemplifies the grandeur of the North Cascades, hitched a ride from Mexico, and probably without documents. It slipped north, five or ten feet at a time. This ‘suspect terrane’ was quite determined. It was playing the long game.

So it seems that chunks of this snowy Alpine range are tropical in origin. Some chunks came from Mexico, and some came from far out in the Pacific. The greenschist of Mount Shuksan started out as a terrane of ocean-floor basalt that got intimate with North America about 100 million years ago, more or less. As it turns out, the North Cascades, like the West coast cities of Seattle, Vancouver, and San Francisco, has a long history of immigration.

The hike from Artist Point to the Lower Curtis Glacier—a linear distance of only six miles—moves through at least four different rock types. In the process, it traverses an ancient caldera, crosses a pluton of igneous rock, and ends up on a vast pancake of ice where huge boulders of greenschist tumble from the cliffs above, and then bounce off the glacier, shattering as they hit slabs of granite below. The ice is dimpled by thousands of small projectiles.

Throughout the geological crazy quilt that is the Mount Shuksan region, narrow tongues of one rock type intrude into another. Seemingly random pockets of one type are nestled within another. The land is dissected by faults running in multiple directions. Because of the extreme topography, rockfall and erosion carry rocks of one sort far from their original placement.

One rock type may smear into another. On the way to Tomyhoi Peak, in a place where landslides are funneled through a cleft in the cliffs, one such smear has created a unique soil blend that has brought together many different species of fern that are not usually found together. This small pocket holds greater fern diversity than any place in North America.

I always linger in the fern grotto, as I call it. The place has come to be emblematic, to me, of the whole Mount Shuksan region. And let me say that the word grotto is a bit tongue-in-cheek. It has, to me, a vaguely Victorian ring to it. A grotto sounds like a manicured place, a quiet little hide-away where well-mannered people enjoy crumpets and tea. It sounds gentle.

This is not such a place. It’s a rocky outcrop below a large and unstable talus slope. It’s ragged. In the summer, rocks tumble down; for much of the year, avalanches are funneled through the gap in the cliff above. The avalanches carry trees down, snapping them like toothpicks. This grotto is under construction, so to speak. And yet, the delicate ferns grow in the cracks.

I love the juxtaposition of rocks and life. This whole essay has been about rocks, but my experience in these places always involves life: the pasqueflower that grows along a creek, the rotund ptarmigan chicks scuttling around witlessly through the heather. In the pre-dawn hour, plump toads hop along the trail like gray stones moving by magic in the dark. The life is not always well-disposed towards me; once, between Lake Ann and the glacier, while climbing over some rocks, I was walloped by some unseen creature, most likely an insect of some sort. My hand swelled and throbbed, then turned numb and tingly. I just kept on hiking. It got better.

Sometimes the life is vaguely menacing. Also in the pre-dawn hour, I’ve briefly glimpsed the sleek body of a cougar crossing the trail ahead of me. More than once, I’ve encountered black bears. I take great delight in watching mountain goats navigate the steep and polished slabs of granite by the terminus of the Lower Curtis Glacier, where Shuksan Creek tumbles exuberantly into the valley that was once the epicenter of a VE7 eruption. The goats keep their distance, but stay close enough to watch, hoping, perhaps, to chew on a salty pack strap or lick a place on the rock where I might pee.

The greenschist of Mount Shuksan lasts for millennia, while the living creatures (including me) live and die in the blink of an eye. Regardless of duration, both are significant. And they are intertwined, of course. The greenschist, the ignimbrite, the hitch-hiking granite pluton, the tiny saxifrage, the sleek cougar, the indolent toad, the vulnerable ptarmigan, the sure-footed goat, the human who is glad to escape suburbia for a day… all are made of the same stuff.

And all of it is, indeed, a beautiful mess.